3. Arrival in Exile

Aleisk, Kedrovka, Charysh

We stopped at Aleisk, a small town between Omsk and Tomsk having left behind us Novosibirsk and Barnaoul.  We were directed towards an empty barn that appeared to have been used as a joiner’s workshop. We made sleeping bags from our blankets. But what we really needed was a good wash. We were allowed to use the public showers known as ‘bania’ and we really enjoyed it. After two weeks of being confined we felt much better after the shower. My damp hair floated in the wind as we were driven back to our barn on the back of a lorry. We were almost happy more especially as the sky was blue and the sun shining.

We were directed towards an empty barn that appeared to have been used as a joiner’s workshop. We made sleeping bags from our blankets. But what we really needed was a good wash. We were allowed to use the public showers known as ‘bania’ and we really enjoyed it. After two weeks of being confined we felt much better after the shower. My damp hair floated in the wind as we were driven back to our barn on the back of a lorry. We were almost happy more especially as the sky was blue and the sun shining.

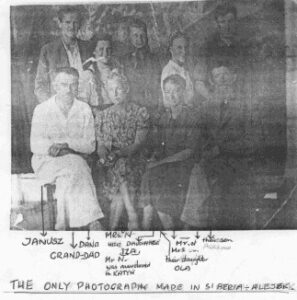

Later we were ordered to have official photographs taken.  My father, my brother and I were photographed along with five other Poles. We were later to find ourselves together doing forced labour in the Kedrovka taiga. All I saw of this small town of Alejsk were the public baths for almost straightaway we and several other families were taken to an unknown destination.

My father, my brother and I were photographed along with five other Poles. We were later to find ourselves together doing forced labour in the Kedrovka taiga. All I saw of this small town of Alejsk were the public baths for almost straightaway we and several other families were taken to an unknown destination.

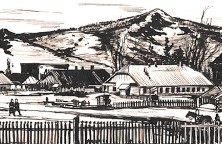

We were driven about 70 kilometres by lorry towards the steppe: a large peaceful plain. The potentially rich pastures appeared to have been left to run wild. We forded the river Charysh. We could see the same state of abandon along the riverbanks – sacks of salt lay around waiting for a hypothetical loading. We were to miss salt terribly throughout our stay in the mountains as we had nothing to flavour our food with. Our journey through the beautiful and high Altai mountains took us to the village of Charyshkoye. There, we were directed to ‘a house of the

people’,  what we would call an inn. In appearance it was clean, but the walls and furniture were infested with bugs which ruthlessly bit and ate us. We were completely defenceless. It was here I made our last appetising sandwiches and snacks – they were too small and too few in number to satisfy our hunger. A hunger which would be a constant companion for many long months.

what we would call an inn. In appearance it was clean, but the walls and furniture were infested with bugs which ruthlessly bit and ate us. We were completely defenceless. It was here I made our last appetising sandwiches and snacks – they were too small and too few in number to satisfy our hunger. A hunger which would be a constant companion for many long months.

Our stay in the Altai mountains – Charyshkoye

The population kept themselves very much to themselves. They didn’t come near or speak to us. All that is except one. He was a young primary school teacher in his twenties who taught near Charyshkoye but, like us, lodged in the ‘house of the people’. He confided in my father and was curious to know how we lived in our country. He let my father know how surprised he was by his answers. He couldn’t believe what we told him about how we lived before: he thought the conditions outside the Soviet Union were worse. This was because they had constantly been told that and it had been repeated endlessly from the loudspeakers which were found everywhere. The radio continually broadcast government programmes and news. My father greatly admired this young man and was surprised by his ability to sift the truth from the propaganda since he had been born under this regime, he’d never known anything different.

Unfortunately, the authorities must have found him dangerous. On our return to Chrayshkoye after our three-month stay at Kedrovka, one of our companions-in-deportation who had been given a job in the small local hospital warned us that the young primary school teacher was lying unconscious in the hospital. He had been tortured: the soles of his feet burnt. He lay in a guarded hospital room. We never found out what happened to him. It can’t have been the conversations with my father that led to his arrest because my father would also have been arrested. No doubt he’d been too frank in talking to people and shown his opposition to Soviet ideology.

We didn’t stay long at Charyshkoye. We were scheduled to move to Kedrovka to do forced labour. I managed to ask someone questions about it. Exceptionally, they answered me and said how beautiful it was and boasted about the Pine trees and nuts.

The reality was totally different! But first we had to get there. We walked behind a horse-drawn cart piled high with our luggage. The path was narrow and stony, but lined by a dense, pretty forest. Snow was still lying in places and wild leeks were pushing their way through. On arrival, several of us were housed in a hut divided into several ‘izby’ (rooms). A large stove -‘ruski’ in Russian – took up the middle of the room and around it were several wooden bunks. We shared the room with another family.

To eat, we went looking for wild leeks. To find them we had to climb higher and higher up the mountains because in July the snow under which they grew was scarce. We diced the leeks, mixed them with flour and a little milk and baked them in the oven. Nevertheless, there weren’t enough of them to satisfy our hunger.

We had scarcely finished sorting out our living arrangements when we were set to work. Near our hut we had to lay the foundations of what was to be a sawmill. we were given some very old spades to do the work. They were wielded by hands totally unprepared for this sort of work. Among these ‘hands’ were a railway executive, a businesswoman, secondary school children – at 16 I was one of the latter.

We set about our work willingly. In any case we had no choice.

I hurt my heel that first afternoon at work. It soon became infected and I was allowed to remain in the hut. That’s how I lost my bread ration, or rather, the flour given to those officially working on the building site. The flour was given to us at irregular intervals: every one or two weeks. We received one glass per person per day. At the far end of our hut lived one local family and another lived nearby in a house next to a small bridge. This family had a garden and one or two cows. That is how we were able to get some milk in exchange for household linen or clothes; for example, we let them have a sheet in exchange for three glasses of milk a day for one week.

Our ‘suppliers’ (those who brought us our small flour ration) would stop at the end of our hut in front of the guard’s lodgings. If we gathered fruit in the forest, they increased our flour ration. Delicious wild strawberries and giant gooseberries as big as small plums were ripening in the mountains. These were collected and taken to a small factory in Charyshkoye and made into jam for those Russian soldiers fighting at the front against the Germans. It was impossible for an ordinary person to eat any of these jams or even any sugar. On one occasion, a female factory worker smuggled out in her hand three cubes of sugar out of compassion for us. They were to be the only ones we ate in our 15 months of captivity and the only ones she dared to bring out from her workplace

If there were lots of fruit in the mountains, we still had to go looking for them and to know the places to find them and also to be guide at gathering them. This enabled us to have an extra ration of flour. One day the smell of the fruit, tiredness, hunger and the heat made me feel dizzy. I dozed off next to a waterfall.

When I woke up I didn’t know where I was or how long I’d been there. On arriving back at the hut my father forbade me to go so far away again. We greatly missed the fruit which supplemented our meagre diet. I could only look from a distance at the splendour of the countryside. I marvelled at the beautiful mountains covered with so many different sorts of trees which autumn clothed so well. Bears were to be found half-way up the mountains in which we lived. They were not the only wild animals. There were all sorts of game and the men dreamed of having a rifle. In our situation it was totally out of the question! The highest summit we could see, and which was always snow-covered, was ‘Bietka’ (Beluka in Russian). Beyond that was China and Mongolia.

So much richness lay before us while we, the deportees, – but also the Russian people- went hungry. Our daily ration of a glass of grey flour didn’t go very far. I kneaded the flour mixed with water and made thin pancakes so there would be more of them. I then cooked them on the hot bricks of the big Russian stove. I also used to heat on these the little amount of milk I’d been able to obtain. We tried to survive on the wild leeks we’d found.

So much richness lay before us while we, the deportees, – but also the Russian people- went hungry. Our daily ration of a glass of grey flour didn’t go very far. I kneaded the flour mixed with water and made thin pancakes so there would be more of them. I then cooked them on the hot bricks of the big Russian stove. I also used to heat on these the little amount of milk I’d been able to obtain. We tried to survive on the wild leeks we’d found.

During the months from July to September 1941 we spent in Kedrovka, we had nothing else to eat. We never saw the hazelnuts we’d been told about. In any case the trees were too far away. I had nightmares because I was so hungry. I would cry out in my sleep ‘Look out! The milk’s boiling over and is escaping up the chimney’.

One day I met a young girl about my age when I was taking some bed linen to the family who lived nearby. We got on well straightaway and met two or three times. But soon my father was asked to stop these meetings. I didn’t understand why and was very unhappy. My father then explained we must avoid any conflict with the local authorities. My new friend must have received the same warning because I never saw her again.

Soon afterwards we left Kedrovka . Was this a result of the agreement between the Allies and the Soviet Union? Who knows? We Poles talked about it secretly among ourselves but really nobody knew anything. We tried to hope but in the meantime our living conditions were not getting any better.